Financial planners know that even intelligent people can become highly irrational when it comes to money. Managing a client’s expectations and emotions is just as important as managing their exposure to markets.

The “bucket strategy” (or “time segmentation strategy”) is one attempt to tackle the tendency of investors to sell out of markets at the worst possible time.

It splits a portfolio into objective-based buckets: simplistically, a conservative bucket (with cash) can be used to fund short-term living costs via a pension while other buckets, such as a more aggressive growth bucket (with shares and property), can fund longer-term requirements. As the growth-oriented bucket won’t be drawn-down for a number of years, there is a greater chance that an investor will be able to ride out any volatility while benefiting from higher long-term returns.

But there is a fundamental misconception that is also beginning to gain traction: that bucket strategies can adequately manage market risk. Bucket strategies may go some way towards managing the behavioural tendencies of investors, but the inherent market volatility that resides in a static asset allocation remain.

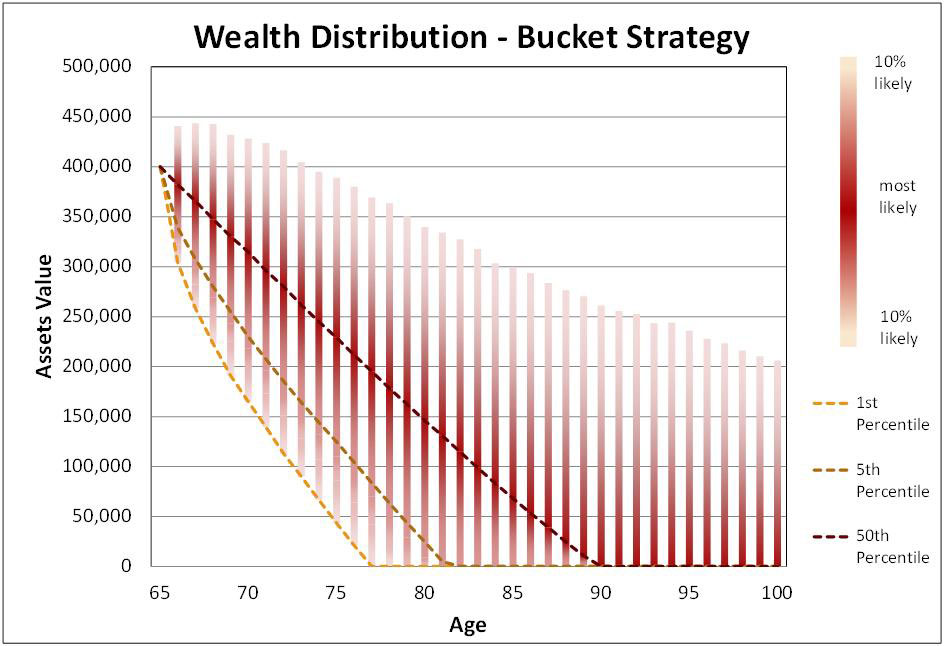

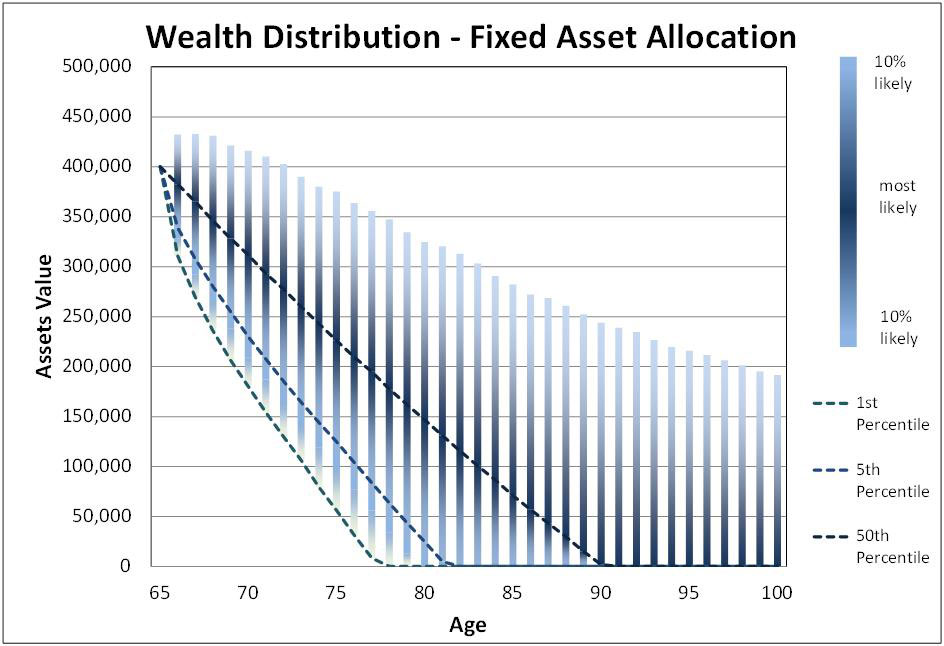

The diagrams in this article show the distribution of a sample client’s residual pension balance after withdrawals using Milliman’s member benefit modelling: a bucket strategy using three buckets (cash, conservative and growth) (Diagram 1), and a static asset allocation strategy (a 70/30 mix of growth and defensive assets) (Diagram 2). The outcomes are very similar, suggesting that the bucket strategy offers little genuine value in managing retirement drawdown risks.

A key assumption underpinning the notion of the bucket strategy as a means of managing market risk is the “mean reversion” concept, which assumes that in a down market, retirees will still have enough cash reserves to meet their pension income requirements until markets recover. Equity markets are supposed to quickly recover (or revert to the mean), mitigating an investor’s need to draw capital from growth assets and crystallize losses.

But the mean reversion assumption is not supported by investors’ recent experience through the global financial crisis. While the S&P/ASX 200 has performed strongly in recent times it has still not returned to the pre-GFC levels it reached seven years ago. Theoretical evidence for the long-term mean reversion of equity markets is similarly unconvincing. The nature of long-term returns (there aren’t many independent 10+ year return periods we can observe) provides little statistical evidence that markets genuinely exhibit mean reverting behaviour over long periods of time.

A conservative cash bucket strategy typically provides 2-3 years’ cash for an investor to draw-down on before they must start selling growth assets. If an investor enters retirement during such a market downturn, they would need to crystallise capital losses within the growth portion of the portfolio to fund their pension. Regardless, bucket strategies are regularly rebalanced, which effectively increases an investor’s exposure to defensive assets over time.

The inability of bucket strategies to directly manage market volatility is a significant limitation. However, if they can prevent an investor from shifting their money into safe assets when growth assets such as equities are at their worst, then it remains a generally positive plan.

But even here, the need for good financial advice to prevent bad behavioural choices is paramount: by separating out the growth assets into a separate allocation, a downturn can look appreciably worse to an investor when considering growth buckets in isolation.

Clients may be able to more easily stick with their investment portfolios and retirement plans when they know a specific cash allocation will be funding their retirement over the next few years. But it may be a different matter for investors without financial advisers to help them stay the course.

One industry super fund recently launched a bucket strategy product as a “default” retirement option for members not seeking advice. The danger with such products is that an investor can still make asset allocation changes at any time and so may be more tempted to lower their growth allocation when markets are weak.

The underlying intent of any retirement strategy, including bucket strategies, is to balance risk with the desire for longer-term growth which will fund an increasingly long retirement. There are a number of risk management techniques that can be employed to achieve this. Splitting out asset classes through bucket strategies is not one of them.

This article was first published in Professional Planner.